This post explores further topics discussed during a presentation given at the PESC Data Summit 2023.

Technological ecosystems of education institutions in the United States can be very crowded. For example, our data shows that K-12 school districts have up to thirty-eight active solutions implementations, and higher educational institutions have as many as two-hundred and eighty solutions in their ecosystems. Given the need to share data across solutions, such as tracking student progress, this crowded nature of ecosystems poses a significant challenge for educational leaders.

Many organizations are working to help leaders overcome this challenge by establishing interoperability standards that provide a standardized approach for sharing data between solutions seamlessly. Quite often, discussions about these standards focus on more technical aspects, such as the representation, format, definition, structuring, tagging, transmission, manipulation, use, and management of data. This focus makes sense, given its importance in ensuring that standards are helpful.

Yet, focusing on these technical aspects alone may overlook the “so what” question, i.e., what is the value of interoperability, specifically in education? In this week’s post, we will explore how one organization, the Postsecondary Electronic Standards Council (PESC), sought to address this question.

Context

Before diving into the topic, defining the term “interoperability” may be helpful, as it is often vaguely used. In our experience, the best definition of the term occurs in the standard written by the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society (HIMSS), which defines it as “the ability of different information systems, devices and applications (systems) to access, exchange, integrate and cooperatively use data in a coordinated manner, within and across organizational, regional and national boundaries, to provide timely and seamless portability of information and optimize the health of individuals and populations globally.” Likewise, their definition involves four levels of interoperability:

- Foundational (Level 1): Establishes the interconnectivity requirements needed for one system or application to communicate data to and receive data from another securely.

- Structural (Level 2): Defines the format, syntax, and organization of data exchange, including at the data field level for interpretation.

- Semantic (Level 3): Provides for standard underlying models and codification of the data, including using data elements with standardized definitions from publicly available value sets and coding vocabularies, providing shared understanding, and meaning to the user.

- Organizational (Level 4): Includes governance, policy, social, legal, and organizational considerations to facilitate the secure, seamless, and timely communication and use of data within and between organizations, entities, and individuals. These components enable shared consent, trust, and integrated end-user processes and workflows.

Many of the organizations working on interoperability standards in education focus their attention on the first two levels, with some, such as 1EdTech, PESC, and the Common Education Data Standards (CEDS) including semantic interoperability in their efforts, and others (Access 4 Learning, for example) extending to the questions around consent and trust involved in the fourth level of interoperability.

That said, there is still much to do to parse out the end user value of interoperability, such as why it matters for initiatives like lifelong learning and skills-based pathways and how technological innovations such as artificial intelligence may have an impact.

PESC Summit Approach

Founded in 1997, PESC works with different institutions, school districts, vendors, governmental agencies, and other organizations to build and support data standards, specifically, those related to transcript data, national student data system reporting, and student applications to higher education. Each year, PESC organizes data summits, where participants learn about various initiatives, discuss best practices in using their approved data standards, and share thoughts about where their work might head.

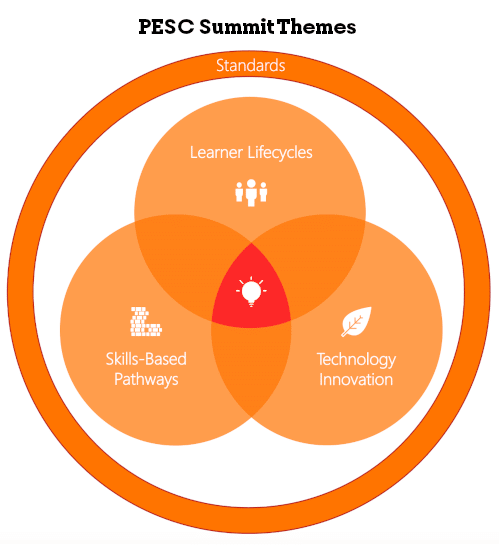

This year’s summit, held in Crystal City, Virginia, was ostensibly aimed at following the approach of previous meetings. But from the outset, it became apparent (figure 1) that this summit would try to view interoperability through the lens of the value it might provide concerning three key areas, i.e., learner lifecycles, skills-based pathways, and technological innovations.

For example, on learner lifecycles, David Moldoff, the CEO and Founder of Academy One, led a group discussion about what learner lifecycles should contain (stackable credentials, etc.) and how interoperability standards might hold value in making these lifecycles frictionless for students. Likewise, Taylor Hansen from the T3 Innovation Network of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce walked through their work to transform the employment marketplace by leveraging interoperability to improve skills-based pathways for learners to enhance their employability and career success. Lastly, others, such as Ross Santy from the National Center for Education Statistics, presented ways attendees could think about why having a standard shared data model and standardized data sharing approach could help students navigate their journeys within educational organizations (K-12, higher education, etc.) and between these organizations (applying to college, for example).

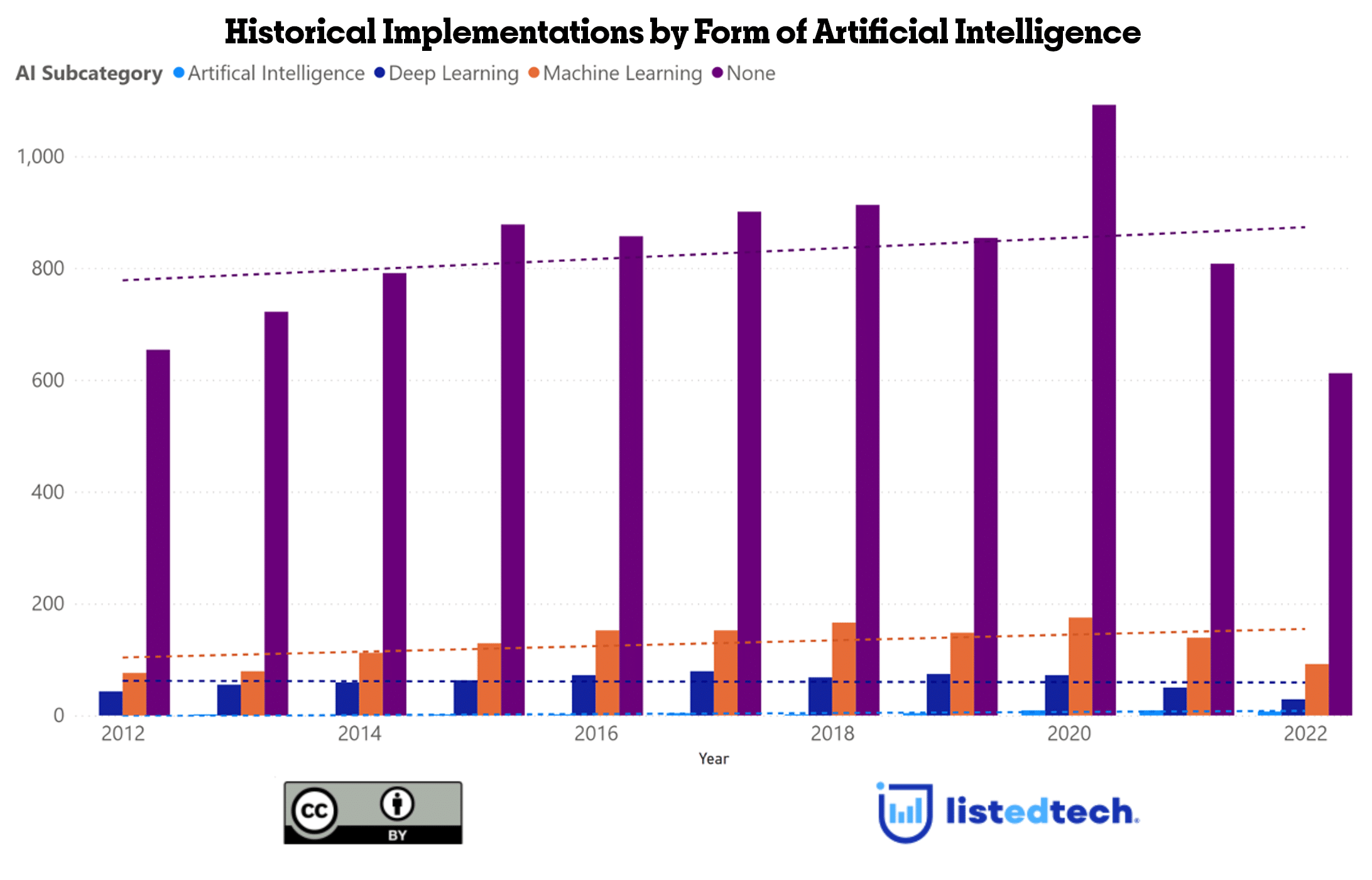

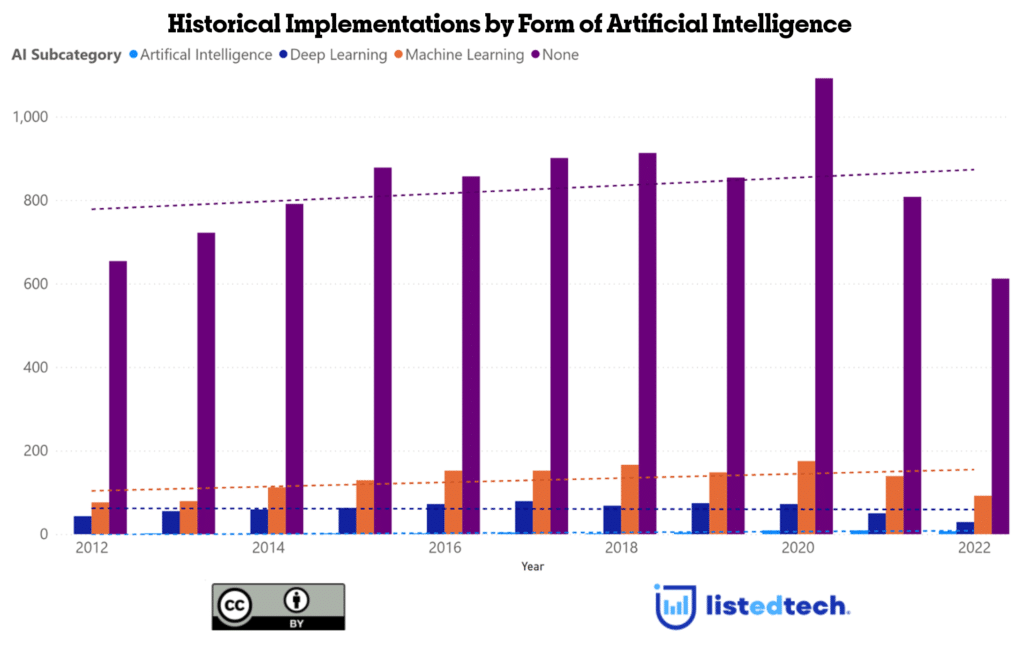

As for the topic of technological innovation, PESC invited us to speak about artificial intelligence, focusing specifically on its current and future role in education. Leveraging our data, we tagged those product categories by the form of artificial intelligence present in their solutions. For example, many admissions systems in the market now leverage machine learning, many enterprise business intelligence systems involve deep learning, and chatbots deploy algorithms that seek to mimic humans in conversations and responding to questions.

As shown in Figure 2, most of the growth in implementations over the past ten years has occurred within those categories without a significant presence of artificial intelligence, such as the student information system category. For those with a presence of artificial intelligence, categories with machine learning show the most significant growth during this period, while categories with deep learning or that seek to deliver the overarching functionality of artificial intelligence (chatbots, etc.) have stayed relatively flat.

Lastly, looking ahead, we posited that there would be three key areas where artificial intelligence may play a role in higher education and how they relate to interoperability. Firstly, artificial intelligence would significantly impact delivering genuinely personalized learning, where users interact with a solution, and the solution develops recommendations and analysis based on that interaction. Likewise, artificial intelligence would help improve decision support for students, informing how they design their decisions, augment them with additional relevant data, discover the best decision, and review the output of that decision. Also, any initiative that sought to increase and deepen student engagement with technology (digital courseware, for example) would benefit from artificial intelligence by leveraging machine learning to improve how students interact with that technology. Lastly, all three critical areas depend on interoperability, as they require accessing, exchanging, and integrating data from disparate solutions for use by artificial intelligence to use in a coordinated manner.

Summary: the Relevance of Interoperability Standards

It is in no way a criticism of any organization working on interoperability standards that they focus on some levels and not others, as sometimes ensuring interoperability on a given level requires a great deal of effort to get right. Likewise, as many of these organizations work together and coordinate their work, they can address many areas of interoperability simultaneously.

However, the exciting aspect of the PESC summit is that it tried to move us from the tactical aspects of interoperability to trying to understand how these tactical aspects might help us deliver value to students, such as assisting them in improving their chances for learning, admissions, transfer, and career success. By viewing interoperability this way, we might refine our approach to addressing gaps in bringing together data to improve our chances of delivering on the promise of ensuring student success for all.